P.O. SEVAGRAM, DIST.WARDHA 442102, MS, INDIA. Phone: 91-7152-284753

FOUNDED BY MAHATMA GANDHI IN 1936

ARTICLES : on Gandhi and South Africa

Read articles written by very well-known personalities and eminent authors about Gandhiji and south Africa.

ARTICLES

Gandhi and South Africa

- Community of Ark: Hind Swaraj Perspectives in Practice

- Gandhi in South Africa

- Gandhi And The Formation of The African National Congress of South Africa

- Mahatma Gandhi, South Africa and Satyagraha

- Thambi Naidu - 'Lion-Like' Satyagrahi in South Africa

- Evolution of Gandhii's Faith : South African Contributions

- Mahatma Gandhi and The Polaks

- Some of Gandhi's Early Views on Africans Were Racist. But That Was Before He Became Mahatma

Further Reading

(Complete Book available online)

- The Making of a Social Reformer : Gandhi In South Africa, 1893-1914

By : Surendra Bhana & Goolam H. Vadeh - Africa Needs Gandhi

The Relevance of Gandhi's Doctrine of Non-violence

By: Jude Thaddeus Langeh Basebang, CMF - Gandhiji And South Africa

By: E. S. Reddy and Gopalkrishna Gandhi - Gandhiji's Vision of A Free South Africa

By: E. S. Reddy and Gopalkrishna Gandhi- (Collection of Articles)

Thambi Naidu : Lion-Like Satyagrahi in South Africa

E. S. Reddy

One of the first satyagrahis in the movement of 1906-14 in South Africa and a most loyal and courageous colleague of Gandhiji was Govindasamy Krishnasamy Thambi Naidoo.1 Apart from defying the law and going to jail many times, he made a crucial contribution in mobilising the Tamils in the Transvaal to participate in the satyagraha and the workers in Natal to strike for the abolition of an unjust tax which caused enormous suffering.

Thambi Naidoo was born in 1875 in Mauritius where his parents had migrated from Madras Presidency.2 According to his daughter, Thayanayagie (known as Thailema), his father was a prosperous fertilisers and cartage contractor in Mauritius. Thambi was his youngest son. One day, his father said to him, “You are my youngest son. You must think of the people before you think of yourself”. Thailema continued:

“My father was very impressed by his father’s seriousness when he said these words and he took them to heart and afterwards built his life on them and taught them to us his children”.3

He went to South Africa with his sister and brother and started business in Kimberley, centre of diamond mines, in 1889 when he was 14 years old. He moved three years later to Johannesburg when gold was discovered in the Transvaal. He started hawking fresh produce, set up shop on Bree Street and gradually expanded his business into that of a produce merchant and wholesaler. He also became cartage contractor.

His obituary in The Star and Rand Daily Mail (1 November 1933) reported that he had founded the Transvaal Indian Congress with H. O. Ally in 1893. If that is correct, this Congress was formed earlier than the Natal Indian Congress which Gandhiji established in 1894.4

His public life began soon after arrival in Johannesburg when Law 3 of 1885, which restricted Indians to segregated locations, was put into operation. He had grown up in Mauritius where there were no humiliating restrictions as in the Transvaal, and he reacted with anger and determination. To quote his daughter Thailema:

“… there was a smallpox epidemic in the Indian location and the Indian traders, not only from the location but those living in Market Street where there was no smallpox, were excluded from the Newtown Market and their livelihood was threatened, while European traders from Market Street were allowed free access. Father was active among the organisers of a protest against this discrimination and when they threatened a protest march in Johannesburg the restrictions were removed from all except residents of the actual quarantine area. He also played a leading part in the formation amongst traders and other workers of the Tamil Benefit Society which looked after its members’ interests…"5

He led a deputation to Johannesburg Municipal Council when he was only 19. He was in a deputation to see President Kruger of the South African Republic and present a petition concerning the Law of 1885.

He collaborated with Gandhiji, when the latter settled in Johannesburg after the Anglo-Boer War, in resisting anti-Indian measures. He became a member of the executive of the Transvaal British Indian Association of which Gandhiji was secretary.

In September 1906, Transvaal Indians held a large mass meeting in Johannesburg in protest against the Asiatic Ordinance which required all Indians to carry certificates with impressions of ten fingers.. The meeting decided to refuse registration under the Ordinance (which later became Asiatic Act) and to go to jail if necessary. Thambi Naidoo seconded the resolution and explained it to the Tamil-speaking people in the audience.6

When the satyagraha started in earnest in July 1907 with the picketing of registration offices, Thambi Naidoo was the chief picket in Johannesburg. He was arrested and served 14 days` imprisonment. On December 28th that year he was charged with Gandhiji for refusing to register and ordered to leave the Transvaal within 14 days.7 On January 10th, 1908, he was sentenced with Gandhiji for disobeying the order. He did the cooking for the nearly two hundred fellow prisoners in the Johannesburg prison.

At the end of January, an agreement was reached between Gandhiji and General Smuts, Minister of the Interior, and the prisoners were released.8 It provided for voluntary registration rather than compulsory registration. Gandhiji understood that the Government would repeal the Asiatic Act when the Indians and Chinese registered voluntarily.

In February 1908, after the Smuts-Gandhi agreement, Gandhiji was severely assaulted by Mir Alan, a Pathan who was probably influenced by false rumours and felt that the agreement was a betrayal. Thambi Naidoo went to his rescue and was also assaulted. Indian Opinion reported on 15 December 1908:

“… Mr. Thambi Naidoo engaged the attention of Mir Alam, who rained blow after blow upon him, which fortunately, Naidoo was able to ward off by means of an umbrella he was carrying at the time. Eventually the umbrella broke and one more blow felled Naidoo to the ground, his head being gashed, and when he was on the ground, further blows were struck at him and he was considerably bruised.”

Almost all Indians registered voluntarily, but Smuts denied that he had promised to repeal the Act and negotiations between Gandhiji and Smuts to find a solution failed.. The Indian community then held a mass meeting at which the registration certificates were thrown into a large cauldron and burnt. Satyagraha resumed.

Thambi Naidoo repeatedly defied the law and went to prison. While the Satyagraha continued, he never thought of personal affairs, but only of the struggle.

It is said that once when he was leading a group picketing the registration office set up under the Asiatic Act, Gandhiji came to tell him that his wife had given birth to a stillborn child. Thambi Naidoo retorted: "Don’t you see I am on duty? Go and bury the child yourself”.9 That does not seem quite correct; Thambi Naidoo was in prison when the child was born.

The reverend Joseph J. Doke referred to this incident in M.K. Gandhi: An Indian Patriot in South Africa, the first biography of Gandhiji:

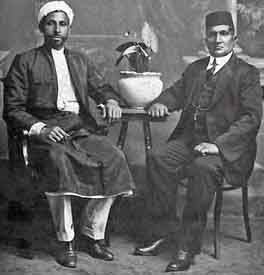

Imam Bawazeer and Thambi Naidoo“When ‘the old offender,’ Mr. Thambi Naidoo, the Tamil leader, was sent to prison for the third time, to do ‘hard labour’ for a fortnight, Mr. Gandhi suggested that we should visit the sick wife together. I assented gladly. On our way, we were joined by the Moulvie and the Imam of the Mosque, together with a Jewish gentleman. It was a curious assembly, which gathered to comfort the little Hindu woman in her home - two Mohammedans, a Hindu, a Jew, and a Christian. And there she stood, her eldest boy supporting her, and the tears trickling between her fingers. She was within a few days of the sufferings of motherhood. After we had bent together in prayer, the Moulvie spoke a few words of comfort in Urdu and we each followed, saying what we could in our own way to give her cheer. It was one of the many glimpses, which we have lately had of that divine love, which mocks at boundaries of creed and limits of race or colour. It was a vision of Mr. Gandhi’s ideal”.

Indian Opinion reported on 8 August 1908:

“When Mr. Thambi Naidoo went to the Fort last week, he left Mrs. Naidoo in a condition wherein she anticipated almost immediate motherhood. On Sunday afternoon she gave birth to a son – still-born. The child was buried at the Braamfontein Cemetery on Monday afternoon.”

A Satyagrahi with Few Equals

Indian Opinion wrote on 21 May 1909:

“Before the movement commenced Mr. Thambi Naidoo was a self-satisfied trolley contractor earning a fat living, and was a happy family man. Today, he is a proud pauper, a true patriot, and one of the most desirable of citizens of the Transvaal, indeed of South Africa. His one concern, whether in jail or outside it, is to behave like a true passive resister, and that is to suffer unmurmuringly”.

Gandhiji reported in his “Johannesburg letter” published in the Gujarati edition of Indian Opinion on 12 June 1909:

“… Mr. Thambi Naidoo has given up smoking, tea and coffee for ever, though, before he went to jail, he could not do without any of these things even for an hour. He has, moreover, pledged himself not to allow his moustache to grow so long as the struggle is on”.

Fifteen years later, Gandhiji described Thambi Naidoo in Satyagraha in South Africa as "lion-like" and wrote of him:

"He was an ordinary trader. He had practically received no scholastic education whatever. But a wide experience had been his schoolmaster. He spoke and wrote English very well, although his grammar was not perhaps free from faults. In the same way he has acquired a knowledge of Tamil. He understood and spoke Hindustani fairly well and he had some knowledge of Telugu too, though he did not know the alphabets of these languages... He had a very keen intelligence and could grasp new subjects very quickly. His ever-ready wit was astonishing. He had never seen India. Yet his love for the homeland knew no bounds. Patriotism ran through his very veins. His firmness was pictured on his face. He was very strongly built and he possessed tireless energy. He shone equally whether he had to take the chair at meetings and lead them or whether he had to do porter`s work. He would not be ashamed of carrying a load on the public roads... Night and day were the same to him when he set to work. And none was more ready than he to sacrifice his all for the sake of the community... the name of Thambi Naidoo must ever remain as one of the front rank in the history of Satyagraha in South Africa”.10

The spirit of Thambi Naidoo and the Tamils can be seen in the letter he sent on 4 October 1909 to Gandhiji, then in a deputation to London. Passive resistance was at an ebb at the time, as most of the merchants were afraid to defy the law for fear of confiscation of their property. He wrote:

“… I beg to inform you that all Tamil prisoners discharged from the prison during your absence are ready to go to jail again & again until the Government will grant us our request. I was in Pretoria on the 22nd and 23rd of last month in order to receive the Tamil prisoners who was discharged on those dates and I did receive them with a bleeding heart. I could not recognise more than about 15 men out of the 60 prisoners who were released. The reason for this was that they were so thin and weak some of them nothing but skin & bone but in spite of this suffering that they have to undergo they were all prepared to go back to jail today… the reason for the prisoners to get weak & thin is the insufficiency of food and of the absence of ghee.”11

Thambi Naidoo was the sole breadwinner of the family. While he went repeatedly to prison, Veerammal, his wife, had to take care of the seven children, but she could not manage her husband’s substantial business as cartage contractor and owner of a fodder store. She began to sell off horses and carts one by one. The family had nothing left. Her brother took them to his home, but he too went to prison and they were homeless again. As many Tamils faced such problems, Gandhiji, with the help of Hermann Kallenbach, established the Tolstoy Farm where former prisoners and families of prisoners could stay.12

Veerammal was a cook in the Farm; Thambi Naidoo was in charge of marketing and sanitation; and their four younger children carried water from springs almost a mile away.

Final Stage of the Satyagraha

Satyagraha in the Transvaal was suspended in 1911 after a provisional agreement between Gandhiji and General Smuts. But the government did not implement the agreement. Meanwhile, the Cape Supreme Court declared marriages performed according to religions which allow polygamy – such as Hinduism, Islam and Zoroastrianism - were not valid in South Africa. That judgment had serious repercussions as most Indian women became legally no more than concubines and their children became illegitimate. The government ignored appeals for legislation to remedy the situation. Gandhiji decided, after consultation with his associates, to invite women to join the satyagraha.

At the same time, the three pound tax which was levied on workers in Natal who had completed indenture, and their wives and children, was causing so much suffering that action had to be taken to secure its abolition. It was, therefore, decided to persuade Indian workers to go on strike until the tax was abolished.

Members of the Thambi Naidoo family, including his wife and mother-in-law, were among the seventeen Transvaal women who volunteered to go to Natal, explain the three pound tax to the workers and persuade them to strike.

Thambi Naidoo led the women and went from mine to mine to persuade the coal miners to suspend work. After the women were arrested and sentenced to three months in prison with hard labour, he continued organising the strike of workers in plantations, railways, municipalities and other locations. He marched throughout Natal addressed huge meetings without any rest and often without food.

He addressed a mass meeting of four or five thousand people in Pietermaritzburg in November and it adopted a resolution calling for a general strike the next day. Workers in sanitary, hospital, electricity departments were, however, requested remain at their posts.

Towards the close of the meeting, Thambi Naidoo was informed that a C.I.D. officer had arrived with a warrant for his arrest issued in Durban. Indian Opinion reported:

“… he exhorted his hearers to have no fear, as he was not afraid to go to jail for the cause. A sensation was created by the announcement, and Mr. Naidoo proceeded to warn the crowd not to initiate any acts of violence, but to remain passive resisters and obey the commands of law and order. Let them, he said, suffer for the cause, but on no account resort to acts of aggression or violations of the law.”

He was later released in Durban and continued with his work. Natal saw the biggest general strike in its history while Gandhiji was in prison.

The strike, and the fearlessness of the workers despite brutality by the employers and the army, helped persuade the government to release Gandhiji from prison, negotiate with him and sign an agreement acceding to the main demands of the satyagraha.

Thambi Naidoo spent a total of fourteen terms in prison during the satyagraha. Seventeen members of his family were reported to have been in prison at one time.

Fighter till the End

After Gandhiji left South Africa in 1914, Thambi Naidoo continued to lead the Indian community while struggling to make a living. Soon after the end of the Satyagraha, he joined the successful appeal to the courts against segregation in tramways and fought for the removal of the colour bar in the municipal market. As there were renewed attempts after the First World War to harass Indians, he was active in mobilising the people to protest.

He was elected President of Transvaal Indian Congress in 1932. He denounced the Transvaal Asiatic Land Tenure Act and the Licences (Control) Ordinance, which added to the disabilities of the Indians and persuaded the TIC to decide in principle on passive resistance. He offered himself and his family to go to jail for the cause. He condemned the decision of the leaders of the South African Indian Congress to join the Colonisation Enquiry Committee, set up by the regime to find ways to induce Indians to emigrate to distant lands like Borneo; from his sick bed in August 1933, and against doctor’s advice, he went to a Conference called by the South African Indian Congress and fought to the end.

He also led the fight, early in 1933, for the removal of untouchability at Melrose Hindu Temple.

He passed away on 31 October 1933, after long illness, and his ashes were buried in the Indian Cemeteryin Brixton, on 1 November. Indian Opinion reported on his funeral on 17 November:

“Great crowds turned out for the funeral of the late Mr. C.K.T. Naidoo, at his residence in 176 President Street. The streets were thronged with people and cars that special policemen were on duty controlling the traffic. The procession was nearly two miles long. It was an awe inspiring sight and a fitting tribute to a great patriot and hero…

“There were 80 cars in the procession besides the horse vehicle. The funeral procession went through President Street right into the heart of the town. Hundreds lined the street.

“As the cortage arrived at Vrededorp the whole of 17th Street from Delarey Street was crowded. Many signs were evident of the great appreciation that men and women had for the man who was determined to lay down his life for the honour of the Indian community in South Africa…

“The coffin was laid in the beautiful courtyard of the crematorium. Mr. M. Nursoo acted as chairman for the great meeting. Speeches were made and the first to speak was Mr. H. Kallenbach, who spoke very feelingly – for does he not know the sterling qualities of Thambi Naidoo. He said that we have to lay to rest a brave and courageous man and above all a man of peace. He was overcome and he stopped. Mr. J. D. Rheinalt Jones also spoke and said that he had great veneration and admiration for Mr. Naidoo who was vice-chairman of the Indo-European Council, one who truly interpreted the great Indian Nation…”

Indian Opinion wrote in an obituary on 3 November 1933:

"With a sturdy physique and brawny arms, he fathered many a weakling and made life in jail easier for him. Thambi Naidoo was always there to finish his own task as well as to help those who lagged behind to finish theirs. During his leisure time he would be reading religious books or singing hymns and keeping gay those who had a tendency of being morose having never suffered jail life. It was indeed a sorry time for those inside prison when Thambi Naidoo was released. But he was never out long. He required no rest. One heard of Thambi Naidoo’s release and within a day or two news flashed once again that he was arrested. This is the life that Thambi Naidoo led from the beginning to the very end of the great struggle in 1914. During the intervals he was the chairman of the Tamil Benefit Society which did a great deal of organising among its own people. During the great strike in 1913 as a protest against the £ 3 tax on Indian labourers, the late Thambi Naidoo played a heroic part. He led the women from Johannesburg and marched from place to place throughout Natal organising strikes without any rest whether by day or by night and often without food. As he was determined so was he fearless”.

A Family of Satyagrahis

Thambi Naidoo inspired many members of his family and friends to join the satyagraha.

His eldest son Coopoosamy (Kuppusamy) began courting imprisonment soon after he turned 16 in 1909.

Narainsamy Pillay, brother of his wife Veerammal, served four terms in prison.

In 1913, when women were allowed to join the satyagraha, Veerammal, his mother-in-law Mrs. N. Pillay, and Mrs. Narainsamy Pillay volunteered and each spent three months with hard labour in the Pietermaritzburg prison. Veerammal was pregnant at the time and took her daughter Seshammal with her. She gave birth to a son the day after she was released from prison. Her mother was the oldest of the women satyagrahis.

Veeramma with her daughter and sonsAt a farewell banquet to Gandhiji on 14 July 1914, Thambi Naidoo offered Gandhiji his four sons – known as “four pearls of Gandhi” – “to be servants of India”. They were: Naransamy, Barasarthi, Balakrishnan and Pakirisamy.

Gandhiji arranged for them to be taken to India and sent to Santiniketan of Rabindranath Tagore until he returned to India and set up an ashram at Kochrab in Ahmedabad in May 1915. There was much sickness in the ashram. Pakiri , in particular, was frequently ill and passed away in March 1916.

The other three boys were sent back to South Africa at the request of the Thambi Naidoo family.

In the continuing struggle for freedom in South Africa, Naransamy and his wife and children, Barsarathi and Thailema went to prison. Even a grandson of Naransamy was jailed as a student leader.

Thambi Naidoo’s family was unique in that for five generations, they sacrificed in the struggle for freedom from racist tyranny in South Africa.

This article is extracted from a book on Thambi Naidoo and family by E. S. Reddy

Figure 2: Thambi Naidu Family

- Thambi Naidoo was always referred to in Indian Opinion as C.K. Thambi Naidoo. But an obituary in the Rand Daily Mail (1 November 1933) gave the full name which, I believe, is the correct name. Thambi Naidoo was the second satyagrahi. The first was Ram Sunder Pandit, a priest who left the struggle after a term of imprisonment.

- Manonmany Naidoo, his daughter-in-law, said that the parents came from Mattur in Tamil Nadu. (The Patriot, New Delhi, 1 October 1988).

- Interview of Thailema to Freda Levishon

- I have been unable to find information on a Transvaal Indian Congress in the 1890s.

C. M. Pillay, a Bachelor of Arts, wrote a letter to Transvaal Advertiser complaining that he had been violently pushed off the footpath. He was apparently mistaken by the Natal Advertiser for Gandhiji, a barrister who was then living in Pretoria. Gandhiji sent two letters to that paper which published them on 16 and 19 September 1893. Mr. Pillay sent another letter to the press on 17 August 1899 and a letter to Gandhiji on December 26, 1897. He signed them as Late Secretary, Indian Congress, Pretoria and Johannesburg. (Gandhi archive at Sabarmati, Serial Numbers 2797 and 3697).

The caption under a photograph of Mr. Ahir Budree in Indian Opinion , 22 October 1913, identifies him as Vice-President of late Transvaal Indian Association. - Interview to Ms. Freda Levishon.

- Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (CWMG), Volume 5, p. 440

- He told the court that he was a married man with five children – the eldest of whom was 13 and the youngest about 18 months.

- The letter to Smuts was signed by Gandhiji, Thambi Naidoo and Leong Quinn, the leader of the Chinese community who also undertook passive resistance against the Asiatic Act.

- Interviews by Ms. Muthal Naidoo and Ms. Freda Levishon with Thailema, daughter of Thambi Naidoo.

- Satyagraha in South Africa

- From Gandhi archives at Sabarmati, Serial Number 5107

- Mr. Kallenbach, an architect and associate of Gandhiji, purchased the farm. He helped greatly in the satyagraha and served a term in prison.