P.O. SEVAGRAM, DIST.WARDHA 442102, MS, INDIA. Phone: 91-7152-284753

FOUNDED BY MAHATMA GANDHI IN 1936

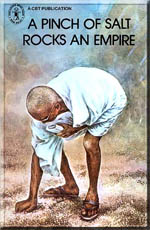

A Pinch of Salt Rocks An Empire

Children's Book : on Dandi March - Salt March

A PINCH OF SALT ROCKS AN EMPIRE

Compiled & Edited by : Sarojini Sinha

Table of Contents

- Map of March Route

- Chapter-1

- Chapter-2

- Chapter-3

- Chapter-4

- Chapter-5

- Chapter-6

- Chapter-7

- Chapter-8

- Chapter-9

- Chapter-10

- Chapter-11

- Chapter-12

- Chapter-13

About This Book

Compiled & Edited by : Sarojini Sinha

Illustration by : : Mrinal Mitra

First Published :1985

I.S.B.N :81-7011-291-5

Published by :Children's Book Trust

Printed at : Indraprastha Press

Nehru House,

4 Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg,

New Delhi,

India

Navajivan Mudranalaya,

Ahemadabad-380014

India.

© CBT, 1985

Download

Chapter - 5

The scene was almost the same all along the 400 kilometer route that the

satyagrahis took to reach Dandi, with excited but orderly crowds, who had been waiting for hours, greeting them at every village. And the message that Gandhiji had for them was the same. Be pure in thought, word and deed; spin yarn and wear khadi; give up liquor, end social evils, be united, peaceful and non-violent; be ready to break the salt law. It was a simple message, simply given. The impact was tremendous.

This message had preceded the marchers. Everyone knew all about the Salt Satyagraha and why Gandhiji and his band of followers were out to break the salt law. The Arun Tukdi (Army of the Dawn) had traveled by rail ahead of Gandhiji giving the villagers the message and making arrangements for the night halt of the satyagrahis.

During the march, the ashram routine was maintained. Prayers were said twice a day. Everyone had to spin on the charka and keep a diary. They walked almost 20 kilometers in the day and several of them were footsore. But Gandhiji, the oldest among them, had no difficulty. He said, teasing his followers, "The modern generation is weak and pampered." There was a horse for Gandhiji's use, but he did not ride it.

Everyday, after morning prayers, Gandhiji addressed the marchers and answered any questions they might have. And the march started punctually at 6 a.m. Time was important. Gandhiji said, "Ours is a sacred pilgrimage and we should be able to account for every moment of our time."

Everyone retired at 9 p.m. But long before the others got up, Gandhiji would be up, often at 4 a.m., to deal with his correspondence. Once he had to write by moonlight as his lamp had gone out for lack of oil and he did not want to disturb anyone.

Every Monday was a day of silence for Gandhiji and a day of rest for the marchers. Five years earlier he had decided on making Monday a day of silence and he would not break the rule for anyone. Even if he had to meet the Viceroy or some other important person on a Monday, he would not speak but write what he had to say. Once, asked why he did not speak on Mondays, he laughed and answered, "I want a day of rest in the week. So many people ask me so many questions that I do not have a moment's peace. I need a day off."

The satyagrahis marched in the cool of early morning and evening, resting at one village in the day and another at night. They slept in the open and ate the simplest food. The villagers were told not to spend anything on the marchers' food or accommodation or donate money. Gandhiji told them, "Money alone will not win

Swaraj. If money could win it, I would have got it long ago. What is required is your blood." All that the

satyagrahis needed was uncooked food and a clean resting place.

The march to Dandi was more than a political campaign. It was aimed at educating the people. By leading a simple life and making a minimum of demands on the villagers, Gandhiji wanted to emphasize his nearness to and fellow feeling with the poor and the lowly. For this reason he criticized some of his companions who ordered fresh milk and vegetables by lorry from Surat and some who, on the slightest excuse, tried to climb into carts or cars passing by. He was angry when, one night, he found a labourer carrying a heavy kerosene lamp for the marchers.

He wanted to emphasize that his movement was for the lowly and poor peasants who formed the majority of the people of India. He was against all exploitation and he saw no reason why imperial exploitation should be replaced by exploitation by Indians.

He said that they would have no moral right to criticize the government for luxurious living if they too were going to live luxuriously. They should live at the same level as the common people in India. They had no right to eat better food than what those among whom they lived and worked ate. "To live above the means befitting a poor country is to live on stolen food," he said. "The battle for independence can never be won by living on stolen food."

At halts all along the way, local leaders met Gandhiji to discuss plans for the civil disobedience campaign they were to launch in their areas after the salt law was broken at Dandi.

In answer to Gandhiji's call more than 300 village headmen resigned their government jobs. Gandhiji had to restrain his over-enthusiastic followers from going too far in their social boycott of government servants who did not resign their posts. At some places, the boycott against policemen and village officials was so strict that they could not even buy food. Gandhiji told the people that it was against religious principles to starve officials. He said, "I would suck snake's poison from General Dyer if he was bitten."

It was General Dyer who had ordered the Jallianwala Bagh massacre eleven years earlier. He and his action will not easily be forgotten, but what, perhaps, brought him freshly to Gandhiji's mind were the words of a Gurkha, Kharag Bahadur, who wanted to join the march after it had started. Gandhiji had said 'no' at first, but relented when Kharag Bahadur said that he wanted to atone for the sins of the Gurkhas who had obeyed General Dyer's order to fire at the peaceful crowd at Jallianwala Bagh.

Thus it was that one more was added to the seventy-eight

satyagrahis who had set out from the Sabarmati ashram.