P.O. SEVAGRAM, DIST.WARDHA 442102, MS, INDIA. Phone: 91-7152-284753

FOUNDED BY MAHATMA GANDHI IN 1936

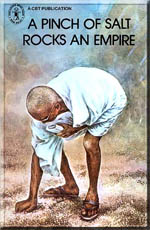

A Pinch of Salt Rocks An Empire

Children's Book : on Dandi March - Salt March

A PINCH OF SALT ROCKS AN EMPIRE

Compiled & Edited by : Sarojini Sinha

Table of Contents

- Map of March Route

- Chapter-1

- Chapter-2

- Chapter-3

- Chapter-4

- Chapter-5

- Chapter-6

- Chapter-7

- Chapter-8

- Chapter-9

- Chapter-10

- Chapter-11

- Chapter-12

- Chapter-13

About This Book

Compiled & Edited by : Sarojini Sinha

Illustration by : : Mrinal Mitra

First Published :1985

I.S.B.N :81-7011-291-5

Published by :Children's Book Trust

Printed at : Indraprastha Press

Nehru House,

4 Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg,

New Delhi,

India

Navajivan Mudranalaya,

Ahemadabad-380014

India.

© CBT, 1985

Download

Chapter - 12

Gandhiji did not sail alone for England. With him were Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya, Sarojini Naidu, his youngest son, Devdas, his British disciple, Madeline Slade, who on joining the Sabarmati ashram had taken the name of Miraben, and his secretary.

As always, Gandhiji wished to lead a simple life. He had given orders that he and his party were to travel by the lowest class, as deck passengers. When he discovered how much luggage his companions had brought with them, he insisted on seven trunks and suitcases being sent back from Aden, the first halt after Bombay.

Gandhiji's followers had brought along his goat, because goat's milk was an essential part of his diet. On the ship, Gandhiji spent most of the day and night on the deck spinning, writing, praying, talking to other passengers and playing with their children.

He reached London on September 12. The British were astonished to see the khadi-clad figure, leaning on a bamboo staff, with his disciples and his goat, getting off the ship. They were even more astonished to think that such a man had come to hold talks with their Prime Minister.

The newspapers were full of photographs and cartoons of the "Mickey Mouse of India". Newspaper men followed him wherever he went. Never before had they seen such a leader, a man who did not need the power of the State to make him great. He had no official position, but people had willingly, almost blindly, followed him to prison. Suffering, and even death, had not deterred them.

Gandhiji was the guest of Miss Muriel Lester, who had visited him in 1926, and he stayed in Kingsley Hall, in the East End, where the poor lived.

It was eight kilometers from the centre of the city and from St. James Palace, where the Round Table Conference was to be held. His friends told him that he would save many hours for sleep and work if he lived in a hotel, but he did not want so much money to be spent on his comfort. Neither would he live in the big houses of his English friends or wealthy Indians. He said he loved living among his own kind, the poor. All that he would agree to was to have a small office at 88, Knightsbridge, so that those who wanted to meet him or interview him would not have to come all the way to the East End slums.

In the mornings, Gandhiji walked through the slum streets and men and women greeted him and smiled at him. He talked to them and visited some of them in their houses. Children crowded round him. When one mischievously asked, "Hey, Gandhi, where are your trousers?", Gandhiji laughed and the children laughed too!

Lloyd George, Britain's wartime Prime Minister, invited Gandhiji to his farm.

Charlie Chaplin, the comedian, wanted to meet him. Gandhiji had never seen a film and had no interest in actors, but on learning that Chaplin had been born in a poor family in the East End, he was happy to meet him.

Among other famous persons who met him were General Smuts, Maria Montessori, and George Bernard Shaw. Lord Irwin, who had been replaced by Lord Willington as Viceroy before Gandhiji left India, also met him.

Gandhiji visited schools and also London University, Cambridge and Oxford. He went to Lancashire to meet the textile workers who were out of work because of the boycott of foreign cloth in India. He explained to them the reasons for the boycott and spoke with such conviction, kindness and directness that he got a wonderful welcome from the people he had put out of work. They told him that they would have done the same thing had they been in his place. It was a measure of the greatness of the English people and their sense of fair play that they could see the point of view of the other party even when that meant suffering for them.

King George V had misgivings about including Gandhiji in the list of Round Table Conference delegates invited to a reception at Buckingham Palace.

When Sir Samuel Hoare, Secretary of State for India, told the King that Gandhiji could not be excluded, he asked, "What! Have this rebel fakir in the palace after he has been behind all those attacks on my loyal officers?

"I am afraid so. It would be a mistake not to invite him, Your Majesty," Sir Samuel replied.

The King then said that he could not invite to the palace a man "with no proper clothes on and bare knees."

Sir Samuel said, "Your Majesty, he, not you, will feel the cold, so why worry?"

So Mahatma Gandhi received his invitation and went to Buckingham Palace in his khadi dhoti and shawl. Towards the end of the reception, the King said, "Remember, Mr. Gandhi, I won't have any attacks on my Empire."

Gandhiji said politely, "I must not be drawn into political arguments in your Majesty's Palace after receiving Your Majesty's hospitality."

Later, asked by a correspondent whether he had felt the cold at Buckingham Palace, Gandhiji laughed and said, "No, His Majesty had enough clothes on for both of us."

Gandhiji concentrated more on convincing the British people of the justness of India's cause than on the discussions at the Round Table Conference. He explained it by saying to an audience, "I find that my work lies outside the conference. This to me is the real Round Table Conference. The seed which is being sown now may result in softening the British spirit..... and in preventing the brutalisation of human beings."

Gandhiji gave lectures, speeches, press interviews, went on trips, met people and answered innumerable letters addressed to him. All this kept him busy for twenty-one hours of the day, leaving him with barely three hours for sleep. His aim was to convince the British people and the world that India had to be free. She needed independence just as any other nation did. He gained many friends and sympathizers.

He said in a radio address to the United States that world attention was focused on India because "the means adopted by us for attaining liberty are unique...Hitherto nations have fought in the manner of the brute. They have wreaked vengeance upon those whom they have considered to be their enemies...We in India have tried to reverse the process... I personally would wait, if need be for ages, rather than seek to attain freedom for my country through bloody means. I feel...that the world is sick unto death of blood spilling. The world is seeking a way out and I flatter myself with the belief that perhaps it will be the privilege of this ancient land of India to show the way out to the hungering world."

He ended with the words, "May I not then, on behalf of the semi-starved millions, appeal to the conscience of the world to come to the rescue of a people dying to regain its liberty?"

However, the British were not willing to make India free. As they saw it, the purpose of the Round Table Conference was "constitution-building" for India.

Of the one hundred and twelve delegates few sided with Gandhiji to resist the forces that were working for the status quo.

The Muslims were given separate electorates. The untouchables also demanded separate electorates. All this strengthened the feudal and divisive forces.

The Round Table Conference was a failure. Gandhiji left England on December 5 disappointed that he had not succeeded in bridging the gulf between Hindus and Muslims and that India was being denied her freedom.

Gandhiji traveled across France, Switzerland and Italy and met many important people before he sailed from Brindesi in Italy for India.