P.O. SEVAGRAM, DIST.WARDHA 442102, MS, INDIA. Phone: 91-7152-284753

FOUNDED BY MAHATMA GANDHI IN 1936

The Story of Gandhi

THE STORY OF GANDHI

Written by : Rajkumari Shanker

Table of Contents

- Birth And Childhood

- Preparation for England

- In England

- Back In India

- In South Africa

- In India

- Back In South Africa

- Indian National Congress

- In South Africa Again

- Assault

- Tolstoy Farm

- Returned To India

- Establishment of Satyagraha Ashram

- Benaras Speech

- Champaran Satyagraha

- Ahmedabad Mill-Workers Satyagraha

- Rowlatt Act

- Jallianwalla Bagh Massacre

- In Prison

- Salt Satyagraha

- Sevagram

- Cabinet Mission Plan

- Quit India

- He Ram!!!

About This Book

Written by : Rajkumari Shanker

First Edition :1969

I.S.B.N :81-7011-064-5

Published by :Children's Book Trust,

Nehru House, 4

Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg,

New Delhi 110 002,

India.

© CBT, 1969

Download

Chapter-7: Back in South Africa

The Europeans in South Africa heard about Gandhi's return. They had also heard about his propaganda in India against the Natal whites. Meetings were held to discuss how to deal with him when he came back.

In the meantime there were rumors that Gandhi was coming back with two shiploads of Indians to settle down there. It was true that some Indians were going to Natal and that they were in two ships, but he had nothing to do with them.

Gandhi's ship cast anchor off Durban on December 18. The passengers were not allowed to land before a thorough medical examination had been made, for they dad arrived from Bombay where there was plague. The ship was held in quarantine for five days.

The whites in Durban had been agitating for the repatriation of Gandhi and other Indians, and this agitation further delayed the landing. Gandhi was accused of having excited anti-European sentiment in India. At last, after a delay of twenty-three days, the ship was permitted to enter the harbour. However, a message reached Gandhi advising him not to land with the other's but to wait until evening, as there was an angry mob of whites at the dock.

Kasturbai and the children were sent to the house of Gandhi's Parsee friend, Rustomji. Later, accompanied by Mr. Laughton, the legal adviser of Dada, Abdulla & Co., Gandhi went ashore.

The scene looked peaceful, but some youths recognized him and shouted, 'Look, there goes Gandhi!'.

Soon there was a rush and much shouting. As Gandhi and his friends proceeded, the crowd began to swell until it was possible to go any further.

Suddenly Laughton was pushed aside and the mob set upon Gandhi.

They pelted him with stones sticks, bricks, and rotten eggs. Someone snatched away his turban, others kicked him until the frail railing of a house. The fury of the whites was unabated and they continued to beat him and kick him.

'Stop, you cowards!' cried a feminine voice. 'Stop attacking him!'

It was the wife of the Superintendent of Police. She came up and opened her parasol and held it between Gandhi and the crowd. This checked the mob. Soon the police arrived and the crowd was dispersed.

Gandhi was offered shelter in the police station, but he declined the offer.

'They are sure to quieten down when they realize their mistake,' he said.

Escorted by the police, he reached Mr. Rustomji's house, where a doctor attended to his injuries.

Late in the evening, the whites surrounded the house.

'We must have Gandhi,' angry voices demanded.

The mob was getting more and more threatening.

'Give us Gandhi or will burn down the house,' they shouted.

Gandhi knew that they might carry out their threat. To save his friend's house, he slipped out in disguise, eluding the crowd.

Two days later a message came from London. Joseph Chamberlain, then Secretary of State for the Colonies, asked the Natal Government to prosecute every man guilty of attacking to Gandhi. The Natal Government expressed their regret to Gandhi for the incident and assured him that the assailants would be punished.

When Gandhi was called upon to identify the offenders, however, he would not do so.

'I do not want to prosecute anyone,' he told the Natal Government. 'I do not hold the assailants to blame. They were misled by false reports about me and I am sure that when the truth becomes known they will be sorry tort her conduct.'

Gandhi's statement suddenly changed there atmosphere in Durban. The press declared Gandhi innocent and condemned his assailants. The Durban incident raised Gandhi's prestige and won more sympathy abroad for the Indians in South Africa.

As the struggle in South Africa continued a change4 was coming over Gandhi. He had begun with a life of ease and comfort, but this was short lived. As he became more and more involved in public activated, his way of life became simple. He started cutting down his expenses. He took to washing and ironing his own clothes, and he did I to badly became quite an expert at this and his collars were no less stiff and shiny than theirs.

Gandhi once went to English barber in Pretoria. The barber insolently refused to cut a 'black' man's hair. Gandhi at once bought a pair of clippers and cut his own hair. He succeeded more or less in cutting the front part but spoilt the back. He looked very funny and his friend s in court laughed at him.

'What's wrong with your hair, Gandhi? Have rats been gnawing at it?' they asked.

'No,' said Gandhi proudly, 'I have cut my hair myself.' Then Gandhi tried changes in his food. He started taking uncooked food. He believed that if a man lived on fresh fruits and nuts he could master his passions and acquire spiritual strength. He made many experiments with his diet. He even came to the conclusive that fasting increased one's will power.

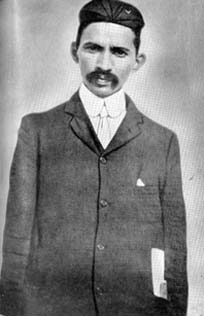

While he was thus experimenting with himself, the Boer war broke out. The Boers were South Africans of Dutch origin. They were fighting the British.

Neither of these two white nations had treated the Indians well. Gandhi did not want to support either of them, but his loyalty to the British made him organize an Indian ambulance corps to help them. To his puzzled followers, he said:

'India can achieve complete emancipation only through development within the British empire. Therefore we must help the British.'

The British won the war and the ambulance corps was disbanded. The newspapers in England praised the services rendered by the Indians. The relations between the Indians and the Europeans had now become more cordial, and the Indians believed that their grievances would soon be removed.

It was now 1901; six years after Gandhi had brought his family to Durban. Now he felt that his future activity lay no tin South Africa but in India. Also, friends in India were pressing him to return home. When he announced his decision to his co-workers, however, they again pressed him to stay on.

After much discussions they agreed to let him go, but only on condition that the would come back to South Africa if the Indians there needed his help. He agreed to this. There were farewell meetings and presentations of gifts.

The gifts were so many and so valuable that Gandhi felt he should not accept them. He wanted to give them back to the people who had presented them, but they would not allow him to do so. He then prepared a trust deed, and all the gifts were deposited with a bank to be used for the welfare of the Indian community.

Figure 2: With the Indian Ambulance Corps, Boer War, 1899